Northern Flicker North America’s Beautifully Colorful Woodpecker

The Northern Flicker is a bird that is called by many names. In Alabama, it is the state bird, known affectionately as the Yellowhammer a nickname dating back to the Civil War when Confederate soldiers from Alabama wore uniforms with yellow trim that resembled the bird’s wing flash. In other regions, it has been called…

The Northern Flicker is a bird that is called by many names. In Alabama, it is the state bird, known affectionately as the Yellowhammer a nickname dating back to the Civil War when Confederate soldiers from Alabama wore uniforms with yellow trim that resembled the bird’s wing flash. In other regions, it has been called the Harry-wicket Gaffer Woodpecker and over 100 other colloquial names.

This abundance of names speaks to the bird’s visibility and charisma. The Northern Flicker bridges the gap between the deep forest and the suburban lawn. It brings a tropical flair to the temperate woodlands with its polka-dotted chest and flashing wings.

The Flicker Split: Yellow-Shafted vs. Red-Shafted

For decades, bird books and guides treated these North American flickers as two separate species: the eastern Yellow-shafted Flicker and the western Red-shafted Flicker.But now birders consider them to be a single species the “Northern Flicker.Although they still look different, there is a large area between their ranges where the two species meet and birds with mixed characteristics are found.

The Yellow-Shafted Flicker (Eastern Group)

If you live east of the Rocky Mountains, the flickers you will see are usually Yellow-shafted. Here’s how they look:

- The Flash: When they fly, the underside of their wings and tails flash a bright lemon-yellow.

- The Face: Their face is a light brown (almond) color with a gray cap on top of their head.

- The Nape: They have a bright red crescent-shaped mark on the back of their neck.

- The Mustache: Adult males have a black line running back from their beak that looks like a “moustache.”

The Red-Shafted Flicker (Western Group)

The Red-shafted type of flickers are found mostly west of the Rocky Mountains. They are identified by:

- The Flash: The color on the underside of their flight feathers is very prominent, ranging from a light salmon to a deep brick-red.

- The Face: Their face is gray and they have a brown cap on their head. (This is the opposite of their eastern relatives, the Yellow-shafted).

- The Nape: They do not have the red crescent moon marking on the back of their neck.

- The Mustache: Adult males have a red “mustache” (stripe marking) on their face instead of black.

Designed to Dig: The Flicker’s Unique Anatomy

To truly understand the Northern Flicker, you need to consider its diet. While other woodpeckers have strong necks and chisel-like beaks to help them dig into hardwood, the Flicker has evolved to feed on a different type of food: ants.

About 45 percent of the Northern Flicker’s diet consists of ants, and nature has designed its body anatomy to easily capture and eat them.

The Beak

The Flicker’s beak is slightly curved and is not as sharp as a chisel like the Pileated or Downy woodpecker. The beak functions more like a “hoe” or earth-shaking tool, better suited for digging up anthills or chipping soft rotted wood than for breaking down hard, living wood.

The Tongue

The real wonder of the Flicker’s body is its tongue. Like other woodpeckers, its tongue is unusually long, which is tucked behind its skull when not in use. However, the Flicker’s tongue can extend two inches beyond the tip of its beak.

- Sticky Saliva: Its tongue has a sticky and special chemical (alkaline) saliva, which neutralizes the effect of the ants’ formic acid so that they cannot harm the bird.

- Barbs: The tip of its tongue has fine barbs, with the help of which this bird easily and quickly pulls out ants and their larvae from deep tunnels underground.

You will often see flickers hopping awkwardly on lawns, peering intently at the grass. They are looking for ant trails. Once found, they will dig into the soil and feast, sometimes consuming thousands of ants in a single sitting.

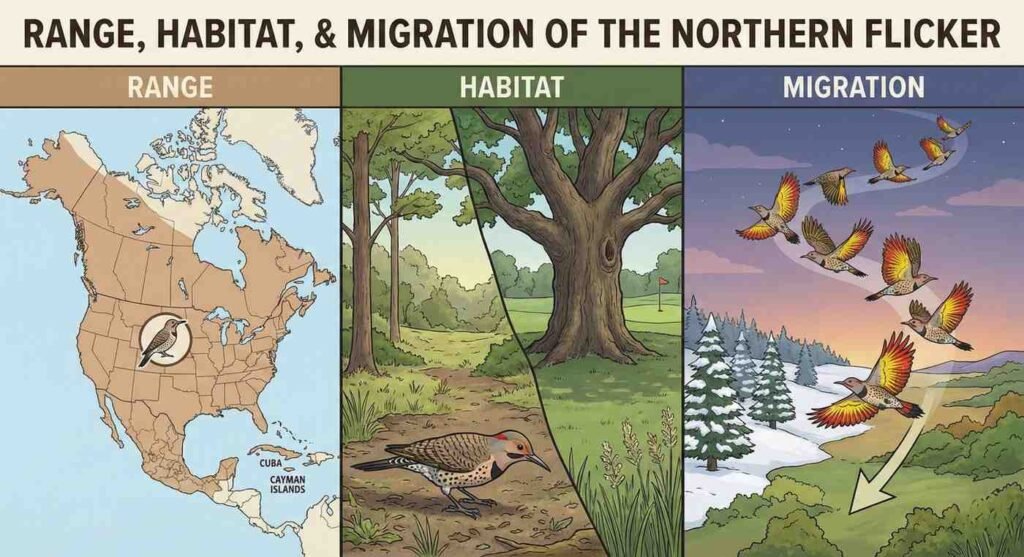

Range, Habitat, and Migration

The Northern Flicker is one of the few woodpeckers found throughout much of North America, from the snowy regions of Alaska and Canada to Mexico, Cuba, and the Cayman Islands.

Habitat Preferences

Unlike the pied woodpecker, which prefers dense, old-growth forests, the Flicker prefers “edge” areas. It thrives in open woodlands, fields, burned areas, and forest edges. Because of this preference, it has learned to live in human settlements; it is often seen in backyards, parks, and golf courses, provided there are old trees for nesting and open land for foraging.

Migration Mysteries

Most North American woodpeckers remain in the same place year-round. If you see a downy woodpecker in July, it will still be there in January.

Flickers from Canada and North America move south in the winter because the ground freezes and they can’t find ants. They travel in small flocks at night. However, flickers from the southern regions do not migrate. They are one of the few woodpeckers that you can see flying high during migration, recognizable by their undulating flight and the bright colors under their wings.

Behavior: Drummers and Dancers

Flickers are noisy and energetic birds. They are not shy about making their presence felt and use both vocalizations and instruments.

Wick-a-wick-a and Kyeer Sounds

The Northern Flicker has two distinctive sounds. The first is a sharp, high-pitched “Kyeer!” (Kyeer), which sounds like the cry of a hawk and is used to signal danger or communication.

The second is a long, drawn-out “Wick-a-wick-a” (Wick-a-wick-a) which sounds like a laugh.

Drumming

Like all woodpeckers, Flickers “drum” to mark their territory. They find a resonant surface—such as a hollow tree, metal chimney, or gutter pipe—and peck at it rapidly. Since they prefer open spaces, they try to make the sound carry far. If you hear a jackhammer sound coming from your roof at 6 a.m. in the spring, it’s a male flicker declaring his territory.

The Fencing Display

A very interesting behavior of flickers is seen during courtship or mating. Two birds (usually two males, or a male and a female) sit face to face on a branch. They raise their beaks, bob their heads, and do a special dance of swaying from side to side. During this, they spread their tails to display the bright yellow or red under their wings.

The Cycle of Life: Nesting and Young

Northern flickers are primary cavity nesters, meaning they dig their own nests rather than using holes that others have dug. This habit makes it a key bird in the ecosystem.

The Architect

They often choose dead or diseased trees (snags) where the wood is soft, and dig a hole 6 to 20 feet above the ground. The digging takes 1 to 2 weeks. The wood shavings that fall during the digging provide bedding for the eggs; these birds do not use grass or straw.

The Family

A pair of flickers usually lays 5 to 8 pure white eggs. Both the male and female incubate the eggs, and the male usually takes on “night duty.” After about 11 to 13 days, the chicks hatch, wingless and completely helpless at birth.

The feeding method for the chicks seems a bit strange and violent. The parents collect ants and place them in their throat pouch (crop), and then they regurgitate a paste of half-digested insects and feed them directly down the chicks’ throats. The chicks grow rapidly and leave the nest about 4 weeks after hatching.

Conservation and Challenges

The northern flicker is currently considered Least Concern because of its high population. However, data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey shows that its numbers are slowly declining. Between 1966 and 2019, there was a decline of about 1.3 percent per year, which means that in some areas their population has been reduced by half.

The Starling Problem The biggest threat to the Northern Flicker is the European Starling. These birds were introduced to America in the 19th century and are very good at taking over other people’s nests. They do not dig their own holes, but steal from others. The starlings often watch the Flicker as he builds his nest. As soon as the Flicker finishes, a flock of starlings will attack, chase him away, and take over the nest. Because they are so numerous and combative, the Flicker’s hard work is often wasted and he is unable to lay eggs.

One Comment