Winter Falconry: The Complete Guide to Cold Weather Training and Hunting (2026)

Winter Falconry: The Ultimate Test of Resilience Winter falconry is defined by a specific moment in mid-January that separates the hobbyist from the master. You are standing thigh-deep in snow, the wind is howling through the barren trees, and the thermometer reads 15°F (-9°C). Your fingers are numb, your toes are stinging, and you haven’t…

Winter Falconry: The Ultimate Test of Resilience

Winter falconry is defined by a specific moment in mid-January that separates the hobbyist from the master. You are standing thigh-deep in snow, the wind is howling through the barren trees, and the thermometer reads 15°F (-9°C). Your fingers are numb, your toes are stinging, and you haven’t seen a rabbit in two hours.

A rational person would be indoors. But falconers are not rational. We are there because winter is the crucible. It is the season that burns away the amateurs and reveals the true practitioners.

In the summer, the sport is theoretical. In the autumn, it is hopeful. But in the cold, it is raw, elemental, and unforgiving. This guide is your roadmap to navigating the 2026 season, blending ancient wisdom with modern technology to ensure you and your bird don’t just survive the cold, but master it.

The Winter Engine: Biology of the Cold

To understand winter falconry, you must first understand the engine you are operating. A raptor is not a dog; it is a high-metabolism predator that runs hot (approx. 105°F). In winter, the bird is fighting a constant battle against entropy.

Why Flying Weight is a Moving Target

For years, apprentices were taught to find a “flying weight” and stick to it. In the winter of 2026, we know better.

- The Floating Scale: Your bird’s weight must be dynamic. As the temperature drops, the weight must rise. A Red-tailed Hawk that flies at 1000g in October might need to be 1050g in January to have the same energy level.

- The Reserve Tank: A bird flown at “summer weight” in sub-zero temps is a bird with no safety margin. If they get wet, lost, or miss a meal, they lack the fat reserves to generate the heat needed to survive the night. Always err on the side of a heavier, more robust bird in the cold.

The Language of Cold

Your bird cannot speak, but it signals distress clearly if you know what to look for:

- The Sphere: A bird that remains fluffed into a tight ball, even when seeing game or food, is struggling to retain core heat.

- The Shiver: If you see the breast feathers vibrating, the bird is shivering. This is a red alert. They are burning calories faster than they can consume them.

- The Foot Tuck: A bird constantly shifting weight or pulling a foot high into its belly feathers is standing on a perch that is too cold.

The Modern Falconer’s Kit (2026 Edition)

If the falconer is miserable, the bird suffers. When you are freezing, your patience evaporates. You rush the hunt, you fumble the equipment, and you make poor decisions.

Active Heating Technology:

By 2026, the days of wearing six layers of bulky wool are over. The modern falconer relies on active heating.

- Heated Vests: A slim, battery-powered vest keeps your core warm, which signals your body to send warm blood to your fingers.

- The “Hybrid” Glove System: You need dexterity to tie knots, but warmth to survive. Use a thin, electric-touch liner glove inside a massive, sheepskin-lined mitt. The bird stands on the mitt; you work with the liner.

Telemetry in Winter:

Cold weather is the enemy of lithium batteries.

- The Protocol: Never mount your GPS receiver on the outside of your vest until you are actively tracking. Keep it inside your jacket, pressed against your ribs. Your body heat keeps the battery chemistry active.

- The Redundancy: Always carry a traditional UHF/VHF radio receiver as a backup. In a blizzard, satellite signals can be blocked by heavy snow clouds, but the old-school “beep-beep” radio signal punches through everything.

Draft-Proofing and Environmental Control

Your hawk spends the vast majority of its life in the mews. If that space isn’t optimized for winter, you are starting every hunt with a bird that is already stressed.

The Draft Killer:

Raptors are built for cold; they are not built for drafts. A draft—a moving current of cold air—slices through their downy insulation like a knife.

- The Test: Use a smoke pen or a lit match to test the air in your mews. If the smoke swirls rapidly, you have a draft. Seal it immediately.

- Ventilation: Do not make the mews airtight (that leads to Aspergillosis), but ensure the airflow is high up and gentle, not blowing directly on the perch.

The Perch Rule:

Never use bare metal perches in winter.

Metal conducts heat away from the feet 50 times faster than wood. A hawk sitting on a steel bow perch at 10°F will develop frostbite. Wrap all perches in natural hemp rope or high-density rubber.

Tactics for the Snow-Covered Field

Hunting in January is a tactical game. The cover is sparse, the ground is loud, and the prey is desperate.

Digging Them Out: Overcoming Reluctant Prey

Rabbits and pheasants know that running burns precious calories. In winter, their strategy changes from “run” to “hide.” They will burrow deep into snow-covered brush piles and refuse to flush until you practically step on them.

- The Strategy: You must work the cover aggressively. Kick the brush piles. Trust your dog when he says something is there.

- The Sun Traps: Game animals are solar-powered in winter. Hunt the south-facing slopes in the early afternoon (1:00 PM – 3:00 PM). This is where game will be sitting to soak up the sun.

The Longwing Advantage

For those flying falcons, winter offers a unique visual advantage. The contrast of a dark falcon against white snow makes tracking easier, and game birds flushing against the white backdrop are starkly visible. However, the lack of thermals (rising warm air) means your falcon must rely entirely on muscle power to gain altitude.

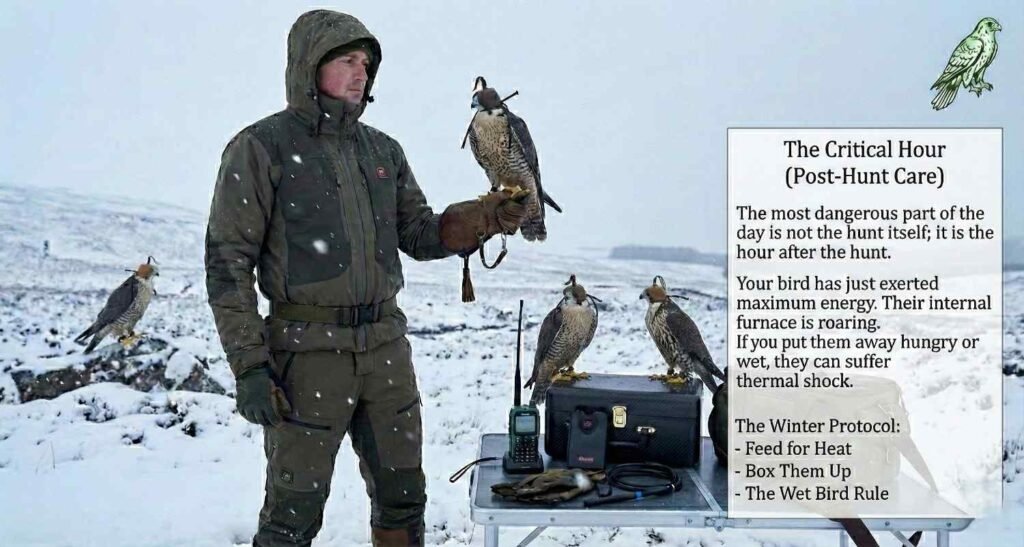

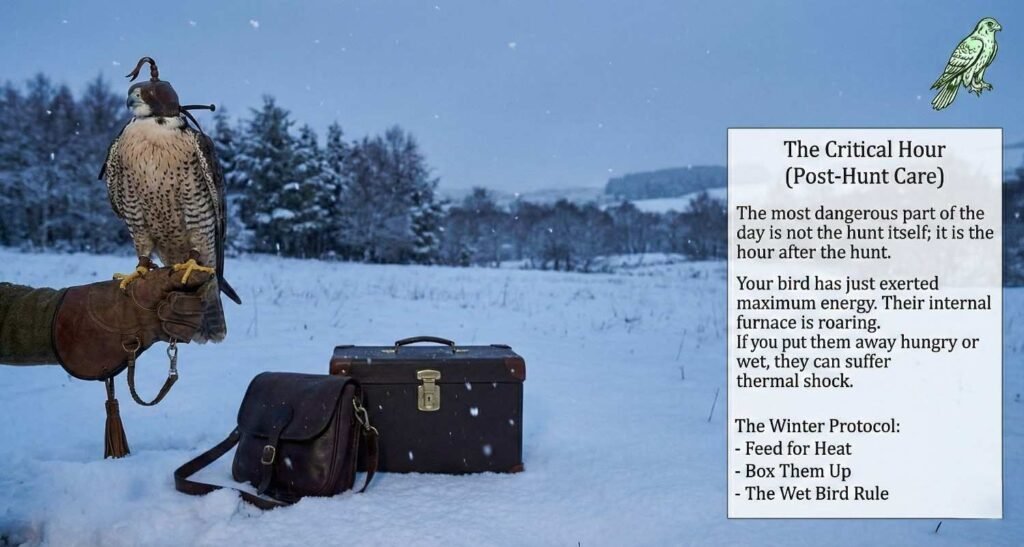

The Critical Hour (Post-Hunt Care)

The most dangerous part of the day is not the hunt itself; it is the hour after the hunt.

Your bird has just exerted maximum energy. Their internal furnace is roaring. If you put them away hungry or wet, they can suffer thermal shock.

The Winter Protocol:

- Feed for Heat: Feed high-quality, “hot” food like mature pigeon, quail, or duck. Avoid washed meat or low-calorie rabbit. A full crop generates internal heat during digestion.

- Box Transport: Transport the bird home in a travel box, not on an open perch. The box protects them from the wind and traps their body heat.

- The Wet Bird: If your bird crashed into snow and is wet, do not put them in the mews. Bring them into a mudroom or heated garage until they are bone dry. A wet bird has zero insulation.

2 Comments